Starting development around 2009, the system has cost at least AUD 2 billion and is touted as being:

A secure online portal, designed to provide a synopsis of your health information to trusted medical professionals.

However, according to the ABC:

It's not a comprehensive picture of your health — it will only contain what you and your doctors choose to upload, and will depend on the quality of those records.

Yet, despite the comprehensive nature of the project little information exists about it; whether on billboards around at airports, or via advertisements on television, social media, or in the traditional newspaper press.

Given that, it must be quite a surprise when you find out about the existence of the system, and that unless they opt-out — by November 15, 2018 — a record will automatically be created for you.

What's In a Health Record?

To be as specific as possible, the record:

can include details of your medical conditions and treatments, medicine details, allergies, and test or scan results, all in one place.

Each record is created from up to 2 years of health information from your Medicare records, which can include:

- Medicare and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) information held by the Department of Human Services

- Medicare and Repatriation Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits (RPBS) information stored by the Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA)

- Organ donation decisions

- Immunisations that are included in the Australian Immunisation Register, including childhood immunisations and other immunisations received

Who Can Update a Record?

Once a record is created:

Healthcare providers such as GPs, specialists and pharmacists can add clinical documents about your health to your record, including: - An overview of your health uploaded by your doctor, called a shared health synopsis. This is a useful reference for new doctors or other healthcare providers you visit - Hospital discharge summaries - Reports from test and scans, like blood tests - Medications that your doctor has prescribed to you - Referral letters from your doctor(s).

Regarding how Healthcare providers can update your record, the My Health Record twitter account says that:

Healthcare providers access My Health Record through their own integrated software system and the timeout rules are subject to the specific clinical system.

I've yet to find out what the “integrated software” is, but I’ll update this post when I do. Then there's one other point to remember. The OAIC (Office of the Australian Information Commissioner) says:

A healthcare provider organisation can upload information to a patient's My Health Record even if the patient has set access controls. A healthcare provider organisation should not upload information to a record if a consumer requests them not to.

How Long Does a Record Last For?

Once created, the records persist until either:

- At least 30 years after an individual's death; or

- 130 years after an individual's birth — if it is not known when they died.

Sounds OK, No?

What Are The Top Concerns?

Being a security researcher, warning bells — which rapidly changed to alarm bells — went off in my mind. You might not appreciate why I was becoming so concerned. You might see the system in a completely different light, as something benign and beneficial.

On the surface of it, the system sounds like a valuable and time-saving system. Given the current system, where records may need to be emailed or faxed, duplicated between a range of different health care providers and specialists, that's understandable.

To be fair, if handled well this could be a massive win for the Australian population. Think about it; all your medical records in one place, able to be easily located and accessed. What's more, if you change doctor you don't have to tell the next one your medical history, as they can see it online for themselves.

If you need emergency care or have to visit several specialists to identify a medical issue, the benefits of the system only increase further. Conceptually, that's something to work towards. However, that's where it all breaks down for me. Here's why.

The Records are Centrally Located

If the records are hacked or lost, consider the implications of such intimate and personal information being available for anyone to see.

Once that information is lost, what might it mean if it was later uncovered by anyone other than the health authorities?

- Could an insurer decline to accept you as a customer, decline to renew your subscription, or inflate your premiums?

- Could you be discriminated against by an employer based on your sexuality, such as being a member of the LGBTIQ community?

- Could you be discriminated against by an organisation based on preconceptions around why you either sought out or were prescribed specific medication?

- Could you be declined service at a government department based on some aspect of your medical history?

And these are just some of the potential implications.

Perhaps you don't think that centrally located health information is a genuine concern. However, it is. Centrally-located information is far easier to hack than data that is distributed.

This happened in the UK twice. The first was when the NHS (National Health System) lost more than half a million pieces of confidential medical correspondence. In that case, up to 708,000 pieces were lost.

The second, also in the UK, was the result of “an IT glitch”. As a result:

GPs will be forced to review the records of over 44,000 records across more than 2,500 GP practices in England following the error, which led to the loss of vaccination information and pathology results.

Is the Information Stored Securely?

As the information is centrally located, it's reasonable to expect that the security measures will be exceptionally well thought out, implemented, reviewed, and improved on a regular basis. However, are they? It's unclear.

The most detailed information that I've been able to find is this:

We use a range of technology to protect the sensitive personal and health information held in the My Health Record system, including:

- Firewalls to block unauthorised access

- Audit logs to track access to records

- Initial and regular anti-virus scanning of documents uploaded to records, and

- System monitoring to detect suspicious activity.

Let's consider each of these points.

Firewalls to Block Unauthorised Access

I'm assuming that they're referring to a standard firewall here, not a Web Application Firewall (WAF). To the layperson, using a term such as "firewalls" might sound impressive, but as I've covered previously, firewalls are a pretty blunt and broad tool.

It makes more sense to use a WAF. If you're not familiar with a WAF, it's a special-purpose firewall for HTTP/S-based applications. Given that, that's what My Health Record is, then it's logical to use one over a traditional firewall.

However, even these have shortcomings, which include:

- They can generate false positives and false negatives

- They can be easily bypassed

- They provide no protection against 0-Day exploits

- Their rules have to be maintained as the application changes

Audit Logs To Track Access To Records

Logging is a must in any application. Developers and systems administrators need this information so that they can ascertain what went wrong, when, where, and why. However, from the title above, it's not clear as to whether the information is user-facing or only for support staff. If it's user-facing, what details does it contain?

Will a user know:

- Whose credentials were used to access their information?

- The location from which the record was accessed, including country and town?

- The IP address of the access location?

In addition to this information, will accesses from anyone other than the owning user require a reason to be provided? If the information is internal, for systems administrators and support staff:

- Is it stored internally in the same data centre as the My Health Record application?

- Is it stored externally, using an external provider such as Loggly, Splunk, Rollbar, or Gralog?

- What information is contained in a log entry?

It's essential to know this because while it's stated that the health records must be stored in Australia, it's not clear that that applies to log information. Secondly, it's quite common for log data to contain sensitive information accidentally, such as user credentials, information that can be used to hack the system.

Initial and Regular Anti-virus Scanning of Documents Uploaded to Records

How regular is "regular"? Hourly? Daily? Weekly? Monthly? Does "Initial" mean on file upload? While it's excellent that anti-virus scanning of (I'm assuming all) documents occurs as a regular part of the service, there are a range of other security best practices to observe. For example:

- Are there restrictions on uploadable file types?

- Are there restrictions on the maximum uploadable file size?

- Where are the files stored after upload?

- How are the files stored after upload?

- Have attacks such as path traversal and path manipulation been accounted for?

System Monitoring to Detect Suspicious Activity

What defines suspicious activity? I asked this of @MyHealthRec recently. If you missed the tweet thread, here are some of the questions that I asked:

What happens when unauthorised access occurs, such as my doctor's credentials being used to access my records from two different locations simultaneously — regardless of whether they were in the same town or a different country?

Will the access be automatically detected and blocked? If so, will I then be notified within a short period after that by phone or SMS? Alternatively, will I be notified via a slower and more indirect means, such as email? At some point, access credentials will slip out, so it's essential to know how this will be handled.

Alternatively, will I have to contact support when I see suspicious activity? This is concerning, as the onus for checking access appears to be placed on the individual. I say this because I found this on a report by the ABC:

You can also set up an email or SMS alert for when a healthcare organisation accesses your record for the first time. The privacy commissioner recommends regularly checking for unexpected or unauthorised access. You can call the ADHA on 1800 723 471 if you think something's gone wrong.

While a good start, this concerns me for two reasons. Firstly, it says that an email or SMS alert is sent when organisations access your records the first time. However,

- What about any time after that?

- What about if fraudulent activity was suspected?

Then, "The privacy commissioner recommends checking regularly for unexpected or unauthorised access.". Human habits being what they are, what percentage of people are going to do this? It's fair to say that it won't be the majority.

Given these two things, it appears that if you find out about suspicious activity on your record or access, you don't consent to, it's only going to be after the fact.

How Can You Control Who Access Your Records, When, and Why?

A post on the ABC raises many concerning questions about who can access your records, along with when, how, and why. It seems that the limitations are far from clear. What is known is that your records are:

reserved for people who work for a registered healthcare provider and who are authorised to provide you with care

If you want to limit access to your data, you can do three things:

- Set a Record Access Code (RAC): This controls which healthcare provider organisations can see your record.

- Set a Limited Document Access Code (LDAC): This controls healthcare providers organisations' access to specific documents

- Set a Personal Access Code (PAC): This allows your nominated representative(s) to access your My Health Record.

That all sounds pretty good, and I agree. However, if you read the information more carefully, you'll find the following:

Please note that when emergency access is granted, any access controls previously set are overridden. This means that any restricted information can be accessed in an emergency.

Emergency access is defined as:

If you have set an access code for your My Health Record and there is a serious threat to your life, health or safety, emergency access to your record may be provided. If you were unconscious, for example, hospital staff may be granted access to your record if there is serious threat to your health or safety.

Now that's perfectly understandable. If you're not able to act on your behalf, then it's essential that someone else can. However, that's not the end of the story. There's another reason for providing emergency access:

Emergency access may also be granted to lessen or prevent a serious threat to public health or safety.

Again, on the surface of it, this sounds reasonable, yet it's still very broad. What's more, there's a "secondary use" provision.

Here's the brief version of what it means:

My Health Record data may be used to provide insight into Australia's health system and the services being provided to improve health outcomes for patients. Find out how My Health Record data can improve health outcomes for all Australians. If you are happy for your data to be used for secondary purposes such as research, you don't need to do anything.

Note how that last sentence ends: "you don't need to do anything". This says that, unless you opt out — assuming that you knew you were opted in — your records are included in information used to provide said insight.

That said, from what I've ascertained, the information is only available in an aggregated and anonymised form; meaning that it should be impossible to link information to an individual. Intentional emphasis added on "should". Research has already shown that anonymised information can be de-anonymised.

This concerns me for several reasons, primarily because...

Exactly Who Can Access Your Records Is Unclear

Users can see who has looked at their records. This information includes:

- When their record was accessed.

- Which organisation accessed it; and

- How the record changed.

However, they won't be able to know, for sure, precisely who accessed their information. In part this makes sense, and in part, it doesn't. Either way, it's concerning.

What's more concerning, however, is the legislation that governs access, the My Health Records Act 2012. This was pointed out recently by Dr Karyn Phelps, former AMA (the Austrlian Medical Association) head.

After reading through the relevant sections of the act, it appears that access may be available to all of the following:

- The Police

- The Australian Taxation Office

- The Courts

- The Veterans Affairs Department

- The Defense Department

- The Department of Human Services

- Medicare

- Any established regulatory body

- A body established by the Commonwealth

- Any Australian Public Service employee in the above departments

- Ministerial Council for data purposes

- Computer programs as designated by the "System Operator."

- Any other person with the consent of the Minister

As Dr Phelps shared in her article:

These provisions break the bond between clinician and patient. The idea that police and security agencies, and the ATO and other agencies could trawl these databases at will is abhorrent. To its great shame, the Parliament passed these provisions.

And according to The Guardian, the Queensland Police Union (QPU), after taking legal advice, says the following about record access requirements:

Access to My Health Record will not be limited to police, as the list of enforcement bodies who may access records includes the immigration department, anti-corruption commissions, financial regulators and any other agencies that impose fines or are tasked with the "protection of the public revenue".

The Guardian's report goes on further to say:

[the QPU has] legal advice that there is nothing in the legislation that requires any enforcement body to obtain a warrant to access My Health Record.

This clearly suggests that a — now removed — article from the Parliamentary Library was correct when it said:

It represents a significant reduction in the legal threshold for the release of private medical information to law enforcement. As legislation would normally take precedence over an agency's 'operating policy', this means that unless the ADHA has deemed a request unreasonable, it cannot routinely require a law-enforcement body to get a warrant, and its operating policy can be ignored or changed at any time.

And here's something concerning that ZDNet wrote recently, to round out this point:

Those types of clauses in other legislation has previously allowed the likes of Bankstown City Council, Victorian Taxi Services, the RSPCA of Victoria, and Australia Post to get their hands on telecommunications data in the past.

Can you see why having such broad access is so concerning?

According to a report by the Guardian, new privacy protections will be added to the controlling legislation to ensure that the service can only be used for medical purposes.

And according to a Media Release by Health Minister Greg Hunt there are two excellent changes to the legislation.

Firstly:

This policy requires a court order to release any My Health Record information without consent. The amendment will ensure no record can be released to police or government agencies, for any purpose, without a court order.

Secondly:

In addition, the Government will also amend Labor’s 2012 legislation to ensure if someone wishes to cancel their record they will be able to do so permanently, with their record deleted from the system.

The changes are yet to be enacted. But it’s heartening to hear that concerns have been listened to.

You May Not Know if Police and Law Enforcement Have Accessed Your Information

According to section 70 of the My Health Records Act:

The ADHA is authorised, by law, to disclose someone's health information if the ADHA "reasonably believes" it's necessary for preventing or investigating crimes and "protecting the public revenue".

On the whole, that sounds reasonable. If law enforcement reasonably believes that by accessing someone's information they can prevent a crime, then it's arguable that they should have access. You'd like to think that they could do their job and protect the public.

However, what does "protecting the public revenue" mean? The closest definition that I could find is this one from the Office of The Queensland Information Commissioner:

The public revenue includes levies, taxes, rates and royalties charged on a regular basis. It does not include occasional charges, such as fines, or the recovery of the occasional overpayment by an agency. Protection of the public revenue includes the activities of agencies and bodies intended to ensure that lawful obligations are met by those subject to the charges, such as routine collection, audits, investigatory and debt recovery actions. Prosecution for failure to pay the charge would fall under the criminal law exception. Activities intended to identify and eliminate inefficient but lawful spending of public money will not fall within these IPPs.

How does that apply to a health record management system?

Apps Can Access Your Data

According to Tim Kelsey, the person in charge of the process, initially, apps which you consent to give access to, can "show" people their records, but won't be able to store them.

According to the ADHA (the Australian Digital Health Agency), any apps that seek to access your data undergo a "strict assessment" and need to abide by a Portal Operator Registration Agreement. The agreement includes that:

They do not download or store My Health Record information on their own system, or pass that data on to a third party.

I see several problems with this situation. Firstly, will users always know — for sure — that they have consented to give apps access to their health records?

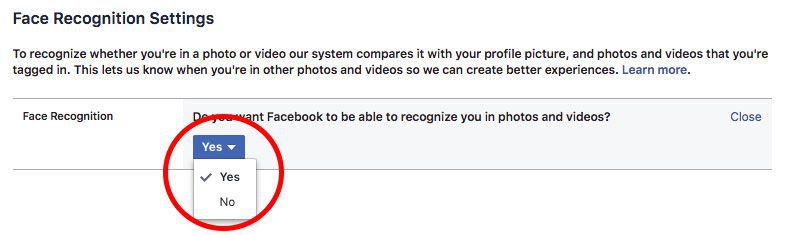

We need only consider how Facebook presents the choice for users to opt-out of facial recognition on their platform, which you can see in the image below.

While you can toggle a Yes/No select box, the text above it, and in several of the steps required to get to this point, make it appear as though this is not the choice that you want to make and that you'll be left out of many positive things if you do opt-out.

Will apps you allow access to your My Health Record data act in the same, or a similar way?

If you're interested, the currently known list of apps that can access your My Health Record are:

- Telstra

- HealthEngine

- Tyde; and

- Healthi

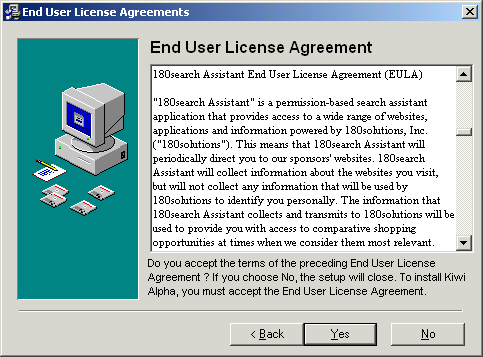

Do We (Really) Understand What We're Agreeing To?

Next, consider privacy policies and terms and conditions that we've all agreed to before we can install or use an app or service. How many of us read them, or read them in their entirety.? Of those that do, how many of us fully understand the implications? For an excellent example, have a read of the license terms for Microsoft Windows.

Alternatively, will the information provided when consent is requested, be too broad in nature? Take the example above of when the HealthEngine app requests consent to access My Health Record account. Is that sufficiently detailed, or provide access to sufficiently detailed information to understand the level of access you're consenting to?

In time, I'm confident that countless users will say that the either never knew, or never fully appreciated, what the app would do, or was asking for.

Now let's consider the condition that apps can only "'show' people their records, but won't be able to store or share them.". Will the government review the source code of every app to know that once the downloaded data is not stored—it has to be downloaded before it can be viewed?

I'd suggest that they won't be given access to the source code, as it would contain intellectual property which the developer(s) don't want to be viewed — for obvious reasons.

Alternatively, will the government test each app before it's allowed to access the platform to check if it stores information locally? Depending on how the application's developed, it might be impossible to know if this happens or not.

And to reiterate, the information must be downloaded so that the user can see it.

And here's a third potential problem: as yet unknown architectural flaws. What if the user installs an app that, seemingly, had nothing to do with My Health Record? And what if that app was able to conduct a side-channel attack and extract and share information downloaded by a legitimate app?

It might seem a bit far-flung, but recent attacks such as Spectre and Meltdown have indicated that these types of attacks are not only possible but that they can happen.

Conclusion

For The Time Time Being - Opt-Out.

I know that My Health Record has the potential to be a significant improvement upon existing practices, such as faxing or emailing records between hospitals, organisations, and relevant government departments. And I'm sure that, if developed properly, it would allow medical professionals to do their work more effectively and efficiently.

However, given the security concerns, lack of documentation, and grey areas that I've covered in this post, along with a significant number of other concerns that I've read through, I'm far too concerned about the downside to opt-in for the potential upsides.

Perhaps you see it differently. Perhaps you feel that Australia's existing privacy legislation provides sufficient protections. If so, then make the choice that you're most comfortable with.

For my own part, I'm opted out until I see these concerns answered and the documentation made much more specific.

- My Health Record image courtesy of myhealthrecord.gov.au..

- Connect HealthEngine to My Health Record image courtesy of the ABC.

- CC Image Courtesy of Ben Edelman.

Further Reading

- My Health Record privacy amendments 'woefully inadequate': Labor (October 14, 2018, by ZDNet).

Are you tired of hearing how "simple" it is to deploy apps with Docker Compose, because your experience is more one of frustration? Have you read countless blog posts and forum threads that promised to teach you how to deploy apps with Docker Compose, only for one or more essential steps to be missing, outdated, or broken?

Are you tired of hearing how "simple" it is to deploy apps with Docker Compose, because your experience is more one of frustration? Have you read countless blog posts and forum threads that promised to teach you how to deploy apps with Docker Compose, only for one or more essential steps to be missing, outdated, or broken?